The first “Church of the Ascension in the City of New York” was not a building. It was a group of people who hoped to proclaim the Good News of God in Christ, striving to seek and serve Christ in all persons, loving their neighbors as themselves.

In the truest sense of the word “church,” that is still the Church of the Ascension to this day.

But we can look at the different buildings consecrated to God where these people have prayed together, sung together, broken bread together, and baptized, married and buried each other. They have each been, in their time, “The Church of the Ascension.”

See also

Pine Street

In 1827, when a group of evangelical New Yorkers, members of the Protestant Episcopal Church, were inspired to form their own congregation, the first French Huguenot parish in the city offered their church building for their services.

This French-speaking parish had itself been founded 140 years earlier in 1687 as “L’Eglise Française a la Nouvelle York,” after the Sun King, Louis XIV, revoked the Edict of Nantes and French Protestants — the Huguenots — fled for America. Established originally on Petticoat Lane (where Battery Place is today, between Broadway and West Street), by 1704 it had moved north to the corner of King Street (now Pine) and Nassau, one block northeast of Wall Street, and was known as “Le Temple du Saint-Esprit.” Ninety-nine years later, in 1803, this French-speaking parish joined the Episcopal Church and changed its name to “L’Eglise Française du Saint-Esprit”: the French Church of the Holy Spirit.

The Episcopal parish of L’Eglise Française du Saint-Esprit still serves a congregation of French-speaking New Yorkers today, now from its home on East 60th Street.

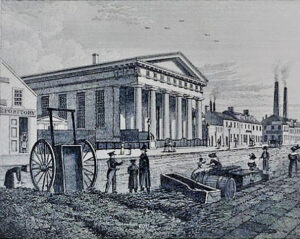

Canal Street

The Church of the Ascension worshiped in the French church for several months while Saint-Esprit awaited a new rector. In the early fall of 1827, the fledgling group of evangelicals incorporated themselves as a parish of the Protestant Episcopal Church: the Church of the Ascension in the City of New York. The population of the city at that time was approximately 200,000.

Just a couple of years prior to this, the canal just north of the Fresh Water Pond and east of the Lispenard Meadows had been bricked over to become Canal Street. Here the Ascension parishioners purchased four lots on the north side just east of Broadway and on April 15, 1828, the cornerstone of the new church was laid by Bishop Hobart. While the church was under construction, and because the French parish needed to make repairs to its interior in anticipation of a new rector, the parishioners and Mr. Eastburn hired a large room on the third floor of the Howard House, on the southwest corner of Howard Street and Broadway, sitting on uncushioned pine benches and kneeling on a sand-covered floor, until their new church was ready for use. (The Sunday School met in the public schoolhouse on Grand Street, east of Broadway, and each Sunday afternoon the rector would address the boys and girls.)

During the next year the church building steadily rose, according to designs prepared by Town and Thompson, architects. The model adopted for the church was that of the ancient Temple of Theseum, a perfect specimen of Grecian architecture, probably inspired by the one built in Athens in 473 B.C. (This style was probably due to Eastburn’s love of the classics; he was known as one of the best Greek and Latin students of his day.) The church was constructed of stuccoed brick and considered quite beautiful; it was said “that young people used to walk uptown of a Sunday afternoon and into the Lispenard Meadows, where the Church of the Ascension was placed, to admire the new building and the colored glass.”

The church was consecrated by Bishop Hobart on May 23, 1829, with a roster of 70 communicants. In those days, Episcopal churches sold or rented pews to families as their primary means of income. A committee was formed to affix prices and sell or rent most of the pews to pay the rector’s salary and for upkeep to the building. They also set aside pews to accommodate “strangers and colored persons.” (Notably, the last slaves in New York City had been freed less than two years earlier, on July 4, 1827.)

Over the next ten years, the parish grew to just over three hundred members. (By 1832, there were no more pews available for sale or rent, and new ones had to be constructed in the gallery in front of the organ.) The Sunday School, in a building erected on the ground lying west of the church, enrolled 185 students, taught by 23 teachers.

On Sunday, June 30, 1839, at 4 p.m. while a service was in progress with a guest preacher ascending the pulpit, a fire broke out in a carpenter’s shop at the rear of the church and spread quickly to the back part of the church building itself. As the psalm concluded but before the sermon had begun, the congregation observed smoke coming in from the east windows. The church building was quickly in flames, but the exit was apparently orderly, without panic, and parishioners hastily gathered up books, vestments and anything else they could move — including a marble baptismal font — as they rushed out. The fire spread to the roof and the church was immolated, leaving only the bare walls. The Sunday School building next door was also destroyed, along with many of the books in its library.

Fifth Avenue

Homeless, the Church of the Ascension was once again blessed by the generosity of another congregation, the Dutch Reformed Church then on the north side of East Ninth Street (Wanamaker Place), between Broadway and Lafayette Street. While worshiping here, after barely a month’s consideration, the vestry decided to build in a new location in the direction the city’s population seemed to be moving. They purchased the lot at the corner of Fifth Avenue and Tenth Street (originally Amos Street) for $32,000 — the same amount they were paid in selling the Canal Street property. (There was a “lively” debate over where to build the new church: on Second Avenue, then the city’s center of fashion, or this new, unpaved “Fifth Avenue” farther west, which at the time extended only as far as a board fence on 23rd Street. Whether true or not, the story passed down alleges the decision was ultimately made by casting dice.)

Not unlike the earliest days of its Canal Street location, lush meadows surrounded the property. A boardwalk across Fifth Avenue provided easy access to Broadway to the east. Henry Brevoort, a parishioner, had built his country estate one block south on Ninth Street in 1834. The neighborhood changed dramatically in the 180 years. The church building and the congregation it held did, too — although, from the exterior at least, the Church of the Ascension today is the only part of Fifth Avenue that looks largely as it did in 1841…despite all the changes occurring around, within, beyond and because of it.

Richard Upjohn

In 1829, a 27-year-old architect named Richard Upjohn moved his family to the United States from his native England. Born in Shaftesbury, he’d been apprenticed to a builder and cabinet maker, eventually becoming a master mechanic. He designed his first church, St. John’s Episcopal, in Bangor, Maine, in 1835.

By 1839, he was commissioned to design the third Trinity Church on the site at the head of Wall Street, its second iteration having been damaged by snowstorms. Such a notable assignment for the “Mother Church” of the Episcopal Church in New York, even if not yet built — along with his designs of great homes in New Bedford, Massachusetts, and Newport, Rhode Island — brought him to the attention of the Ascension vestry. Before Trinity could be completed, Upjohn had designed and constructed the new Church of the Ascension.

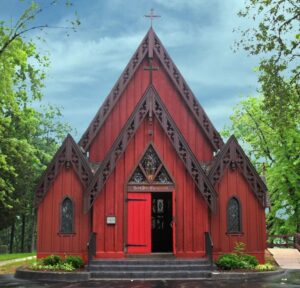

Upjohn was inspired by the Gothic architecture of Europe during the High and Late Middle Ages, roughly the late 12th century to the 16th century. There was already a Neo-Gothic revival going on in Europe, and in America, this “Gothic Revival” was an architectural response to the Federalist and Neo-Classical enthusiasm that had informed so many structures during this nation’s earliest decades — not least the original Church of the Ascension building on Canal Street a dozen years earlier.

Upjohn was a devout Christian. His goal was to contribute designs to the building of one mission church each year. In 1852, he published a book — “Upjohn’s Rural Architecture: Designs, Working Drawings and Specifications for a Wooden Church, and Other Rural Structures,” which allowed poorer parishes to construct churches in wood in a style known as “Carpenter Gothic.” Upjohn was particularly devoted to the Gothic style as the preferred architectural genius of Christianity, so much so that he even refused to design any Unitarian churches on the grounds that their beliefs were, by definition, insufficiently “trinitarian.”

The similarities between Ascension and Trinity Church’s design (including their brownstone construction) are apparent. Both were among his very first churches. But Upjohn went on to create many more Gothic buildings, particularly Episcopal churches, in other stones and in wood as far afield as Wisconsin and Utah, although most are in the northeast U.S.

In 1857, Upjohn, his son and partner, and 12 other architects founded the American Institute of Architects; Upjohn was its first president until he stepped down in 1876.

Low-church Gothic

The cornerstone for the Church of the Ascension was laid March 19, 1840, by the Rt. Rev. Benjamin Onderdonk, Bishop of New York. On Friday, November 5, 1841, Bishop Onderdonk consecrated the completed building “to the worship and service of Almighty God, the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost, according to the provisions of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America, in its ministry, doctrines, liturgy, rites, and usages, and by a congregation in communion with said Church.” In doing so, the bishop was being asked by the rector, churchwardens and vestry to take the building under his spiritual jurisdiction and “to consecrate the same by the the name of the Church of the Ascension, and thereby separate it from all unhallowed, worldly and common uses, and solemnly dedicate it to the purposes above mentioned.”

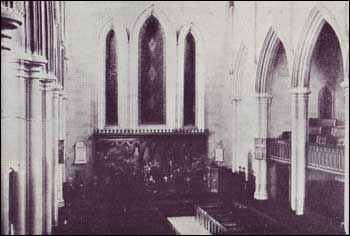

While employing some basic forms of Gothic architecture, Ascension’s exterior and interior were, at the time, without much decoration. The parish’s original rector was still the rector and, as a dedicated evangelical, he was suspicious of anything that seemed overly liturgical or reminiscent of what he saw as “Catholic” worship. In fact, as soon as the vestry had purchased the land for the church building, he purchased the lot directly adjacent on Tenth Street to build a rectory (which is stil just on the other side of the Ascension high altar and mural, neither of which existed in 1841). By some accounts, Upjohn’s purchase and directions to the architect deliberately forced a narrow chancel (the part of the church containing the choir and altar), on the grounds that without much room to maneuver, it could never engage in the more liturgical practices that had recently been popularized by the “Tractarians” of the Oxford Movement. This supposedly offended Upjohn’s Gothic sensibilities, but he complied. The most he could hope to do was decorate the wall directly behind the altar.

Although the windows (including the fake windows above the altar to match those on the north and south walls of the church) had colored glass to let in light, they were without any imagery. Much like our neighbor, First Presbyterian Church to the north on Fifth Avenue (1846), the original interior had a “gallery,” or balcony, on all three sides of the nave.

The Spirituality of Beauty

While the church’s exterior has always been considered well-proportioned, one observer wrote that when the Rev. Dr. E. Winchester Donald became the parish’s fourth rector in 1882:

It was one of the ugliest churches inside to be found in New York, which is saying a good deal, but Dr. Donald had a great love of beauty, and he raised the money and chose the artists who made it what it is today. He found it not only extremely shabby, with holes in the carpet and stains on the walls, but everything about it was ugly—the imitation chancel window with its quarries of crude glass set slap against the wall so that no light came through it, the dreary wooden ‘Tables of the Law’ over the altar, the square platform with a railing around it that they called a pulpit, no stained glass worthy of the name in any of the windows, and all architectural effects marred by the clumsy galleries on either side of the nave.”

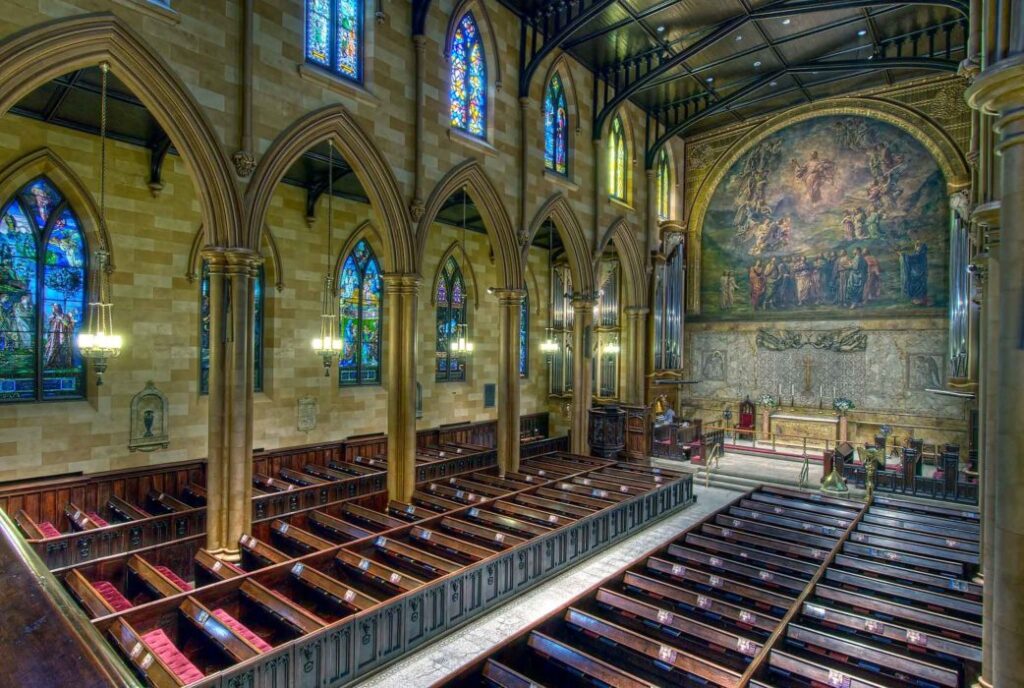

This rector loved the beauty of worship, and realized that truth, goodness and beauty are all of a piece. During his time at Ascension, the south and north balconies were removed, bringing light to the side aisles of the nave; the black walnut reredos with the Ten Commandments and the Lords Prayer inscribed on them was replaced with stone carvings and beautiful mosaics, above a beautiful stone altar. A new pulpit, designed by the noted Beaux-Arts architect Charles F. McKim, was installed, as were the chancel choir stalls designed by his firm and overseen by his colleague Stanford White. (Prior to this, a small choir of usually no more than four voices sang in the rear balcony.)

In addition to the start of replacing the plain colored glass windows with beautiful stained glass imagery, the most notable addition during this period was the addition of the mural “The Ascension,” John La Farge’s great masterpiece, painted in place.

Although Dr. Donald’s rectorship at Ascension lasted barely a decade, it was one of the most transformative for the fabric of the building of any rector, except for the first.

The Church We See Today

Even as things get added and modified by subsequent generations of generous parishioners and friends of the parish, a constant concern for any building of this size is the maintenance of this beautiful interior space and friendly outside presence on the corner of Fifth Avenue and Tenth Street. At various times in the last 180 years, major work to repair the porous brownstone on the exterior has had to be done — sometimes because of the misguided techniques used by earlier generations that later hastened deterioration. In 1985, the parish had to once again prevail upon the generosity of another church (our neighbors, First Presbyterian) and then worshiped in the parish hall while major structural repairs were made to the ceiling and roof of the church, which was at a nearly immediate risk of collapse. Under the leadership of the eleventh rector, the Rev. Andrew W. Foster III, extensive renovations to the church building were undertaken in 2009-10 to address longstanding problems caused by leaks in the roof and windows. At the same time, the world-class Manton Memorial Organ was installed.

The nave — the part of a church the congregation’s pews occupy — is spacious and seats up to 500, but has a feeling of warmth and intimacy not usually experienced in large churches. The choir stalls and organ consoles sit on a raised chancel where a moveable freestanding altar is placed for most services. The magnificent LaFarge mural adorns the west wall with the relatively small sanctuary at its base containing the main altar and surrounded by a communion railing. A smaller altar located at the front of the north aisle is used for services on weekdays and on Sunday at 9 a.m. and occasionally for funeral and memorial services. Columbaria are located in the narthex of the church and in our very intimate All Saints Chapel. The chapel is located through a door off the north aisle as are the sacristy and a corridor that leads to the parish hall. The chapel also has an entrance from Fifth Avenue.

The parish house on West 11th Street was built in 1888, also by McKim, Mead & White. The main public space is the parish hall, a handsome room that comfortably seats 75 for dinner. It was renovated in 1994 when air-conditioning and new lighting were installed. The parish hall is in constant use: for post-service fellowship, vestry meetings, Bible study and book club, AA meetings, music recitals, choir practice, our tutoring program, and even for services during very hot weather. Outside groups sometimes utilize the space as well. The kitchen is in the finished basement, which is also used for storage, choir-robing and the Food Pantry closet. The upper floors provide offices for clergy and staff. The top floor includes an apartment for the sexton, who oversees the buildings’ daily maintenance and security.

Ascension’s rectory, directly behind the altar wall and mural, is a large Gothic Revival townhouse on West 10th Street. The six-story building (from sub-basement to attic) is believed to be New York’s oldest brownstone townhouse in continuous residential use without subdivision or alteration. Garden spaces behind the church and fronting onto Fifth Avenue provide parishioners and visitors a place of respite and quiet reflection.